I thought you were the new method?

In C#, the concept of a virtual method is not new. It’s a simple concept in which a child class may change the functionality of certain parent methods which have the keyword virtual applied. Anytime the child class is instantiated and this method accessed (either in its children or parents), it calls the overridden method by default and not the original. What about methods without the virtual keyword?

On occasion it is necessary to change the functionality of a method already defined in a parent class in it’s children without affecting the parent class’ functionality. The new keyword allows a child class to ignore (or hide) the method of the parent and implement its own anytime the child or its children are explicitly used (this is different than overloading as the new keyword allows a child to re-implement a method with the same signature). At first it seems it would be simple to determine if the parent or the child method would be called, but the method invocation changes depending on scenarios surrounding variable types making it tricky in complex situations.

Take the following piece of code:

public class ParentClass : IHelloWorld

{

public virtual string SayHelloWorld()

{

return "This is the base method.";

}

public string CallMethodToSayHelloWorld()

{

return SayHelloWorld();

}

}

public class ChildClassNew : ParentClass

{

public new string SayHelloWorld()

{

return "This is the new method.";

}

public string SayGoodBye()

{

return "Goodbye.";

}

}

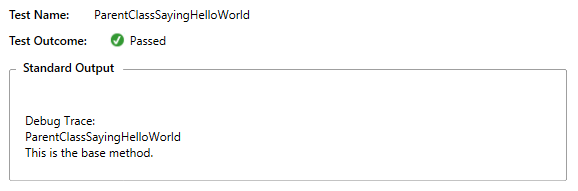

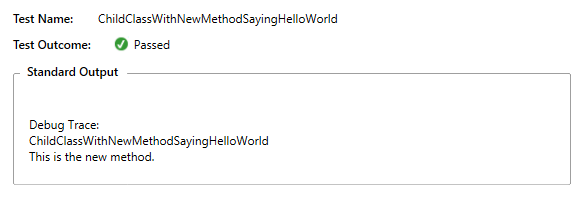

The following two scenarios yield the results you would expect:

public void ParentClassSayingHelloWorld()

{

var parentClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ParentClass();

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(parentClass.SayHelloWorld());

}

public void ChildClassWithNewMethodSayingHelloWorld()

{

var childClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childClass.SayHelloWorld());

}

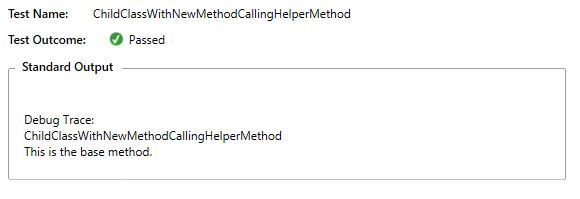

Now what if you implement a method on the parent class which calls the method the child class hides in its implementation?

public class ParentClass : IHelloWorld

{

public virtual string SayHelloWorld()

{

return "This is the virtual method.";

}

public string CallMethodToSayHelloWorld()

{

return SayHelloWorld();

}

}

public void ChildClassWithNewMethodCallingHelperMethod()

{

var childClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childClass.CallMethodToSayHelloWorld());

}

This makes sense. The new keyword only hides the previous implementation of the method from objects accessing itself and its children in the inheritance chain. The parent is unaffected by this as it assumes certain actions will be taken when it calls this method.

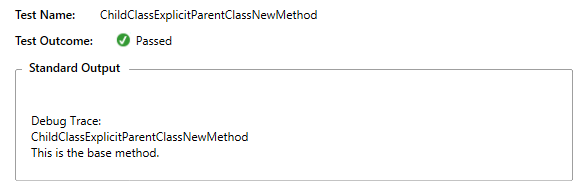

Type declaration When dealing with the new keyword, instantiating an object and assigning a variable with a specific type can alter the effects of how the objects methods’ function.

public void ChildClassExplicitParentClassNewMethod()

{

NewAndOverrideClasses.ParentClass childClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childClass.SayHelloWorld());

}

Even though the object being created is of type ChildClassNew, declaring the variable as its parent type forces the object to ignore the new method and use the one in the parent.

This means that it is possible to create an object and change its behavior based on the calling code. Although this looks strange, in truth, this should be the expected. It follows the same principles as method overloading between parent and child classes. If a child class has an overloaded method which is less restrictive than the parent’s, the child’s method will be called even if the parameter being passed to the method satisfies the more restrictive condition of the parent method if the variable is of type child. (If the parent has void Foo(string s) and the child has void Foo (Object x). The child’s method is less restrictive because System.String can satisfy the parameter of System.Object. Look at the project here for examples.)

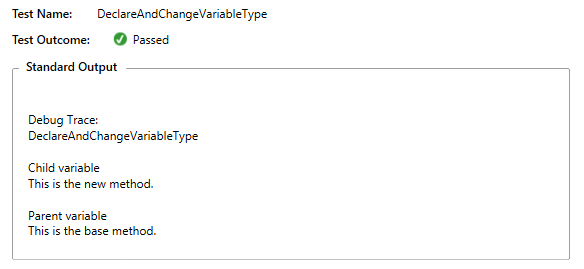

public void DeclareAndChangeVariableType()

{

NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew childClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

NewAndOverrideClasses.ParentClass newChildClass = childClass;

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("Child variable");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childClass.SayHelloWorld());

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("Parent variable");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(newChildClass.SayHelloWorld());

}

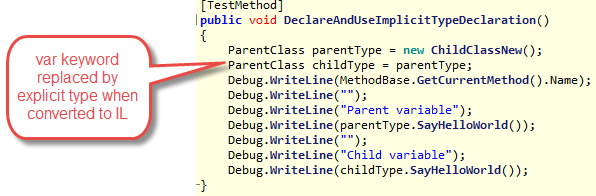

Implicit type declaration With the following code what happens?

public void DeclareAndUseImplicitTypeDeclaration()

{

NewAndOverrideClasses.ParentClass parentType = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

var childType = parentType;

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("Parent variable");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(parentType.SayHelloWorld());

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("Child variable");

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childType.SayHelloWorld());

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine("");

}

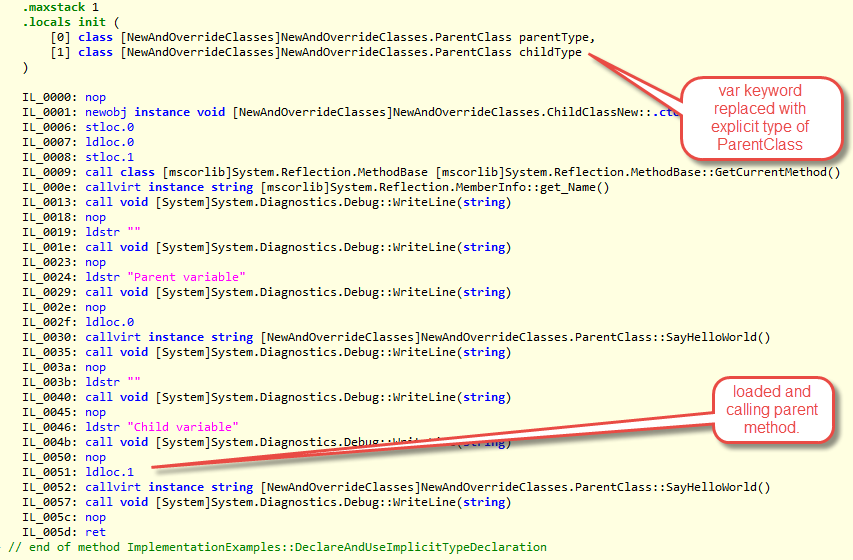

With implicit type declaration, you’re not telling the compiler what you want the variable type to be. You are asking it to figure out what it should be based on the information provided. In the above example var childType = parentType;, if you haven’t read the C# specification on how it works, you could possibly assume it determines the type in one of two different ways. Does it look at what has been explicitly declared as the parentType’s variable type, or does it look at the actual object which is assigned to that variable.

The specification is explicitly clear in how it works:

When the local-variable-type is specified as var and no type named var is in scope, the declaration is an implicitly typed local variable declaration, whose type is inferred from the type of the associated initializer expression.

This means that it looks at the type of the variable and not the type of the object when it is being assigned, so you must explicitly declare the type to change the behavior.

IL code that has been converted by to C# from ILSpy:

Raw IL Code:

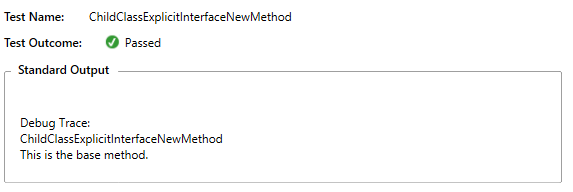

Interfaces Interfaces work in a similar manner to declaring a variable as a parent or a child. If the interface is located on the parent, then it calls the parent’s method:

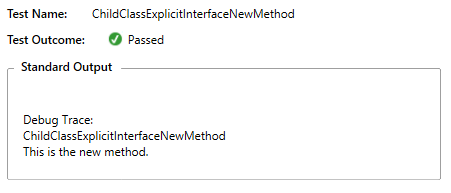

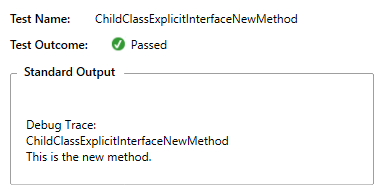

public void ChildClassExplicitInterfaceNewMethod()

{

NewAndOverrideClasses.IHelloWorld childClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childClass.SayHelloWorld());

}

If you reattach the interface to the child class, the behavior of the types declared with that interface change. They now call the child’s method and not the parent.

public class ChildClassNew : ParentClass, IHelloWorld

{

public new string SayHelloWorld()

{

return "This is the new method.";

}

}

Although this makes sense, it leaves the possibility for unintended side effects to happen. Interfaces can require the implementation of other interfaces, and so by attaching a new one to a child class, it is possible to accidentally reattach an existing interface and hide the parent’s behavior.

public interface IHelloWorld

{

string SayHelloWorld () ;

}

public interface IGreetings: IHelloWorld

{

string SayGoodBye();

}

public class ChildClassNew : ParentClass, IGreetings //re-implements IHelloWorld

{

public new string SayHelloWorld()

{

return "This is the new method.";

}

public string SayGoodBye()

{

return "Goodbye.";

}

}

public void ChildClassExplicitInterfaceNewMethod()

{

NewAndOverrideClasses.IHelloWorld childClass = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childClass.SayHelloWorld());

}

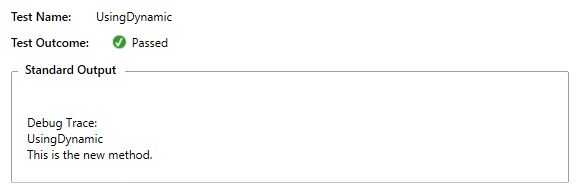

Using Dynamic The dynamic keyword is a divergence from how the of the situations resolve the method. With dynamic there is no compile time resolution and so at runtime the program must determine which method it needs to call.

public void UsingDynamic()

{

NewAndOverrideClasses.ParentClass parentType = new NewAndOverrideClasses.ChildClassNew();

dynamic childType = parentType;

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(System.Reflection.MethodBase.GetCurrentMethod().Name);

System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(childType.SayHelloWorld() as string);

}

Even though the initial variable type was declared as the parent, and if it was called without the dynamic type being used, the parent method would execute. With the dynamic keyword, the behavior changes from the other scenarios where the variable type comes into play.

In certain scenarios, the new keyword can be helpful. Its use should be limited, however, because of it’s complicated rules for which method is called and certain edge case scenarios (such as using dynamic) where actual behavior potentially deviates from prediction.

The code for this post can be found here.