Under The Mattress (or Compiled Code) is Not a Good Place to Hide Passwords

The question comes up from time to time about storing passwords in code, and is it secure. Ultimately, it’s probably a bad idea to store passwords in code strictly from a change management perspective, because you are most likely going to need to change it at some point in the future. Furthermore, passwords stored in compiled code are easy to retrieve if someone ever gets a hold of the assembly.

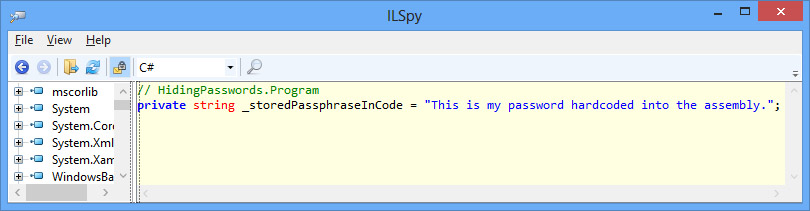

Using the following code as an example:

string _storedPassphraseInCode =

"This is my password hardcoded into the assembly.";

So what about storing the password in some secure location and loading it into memory? This requires the attacker to take more steps to achieve the same goal, but it is still not impossible. In order to acquire the contents in memory (assuming the attacker can’t just attach a debugger to the running assembly), something will have to force the program to move the memory contents to a file for analysis.

Marc Russonivich wrote a utility called ProcDump which easily does the trick. Look for the name of the process (my process is named LookForPasswords) in task manager and run the following command:

procdump -ma LookForPasswords

This creates a file akin to LookForPasswords.exe_140802_095325.dmp and it contains all the memory information of the running process. To access the file contents you can either use Visual Studio or something like WinDbg.

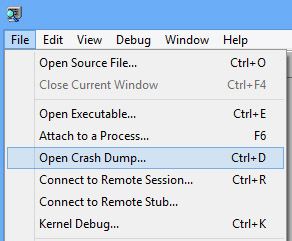

WinDbg:

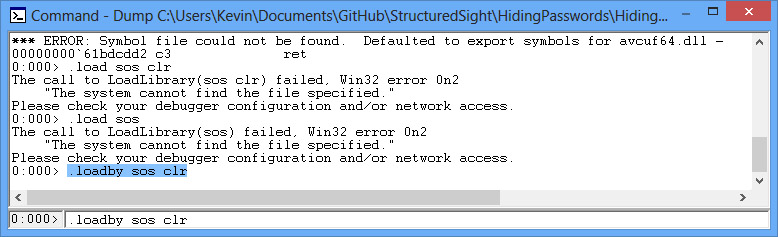

After you open the dump file, you’ll need to load the SOS.dll to access information about the .NET runtime environment in Windbg.

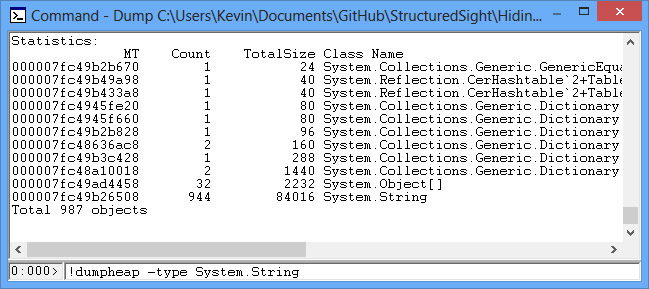

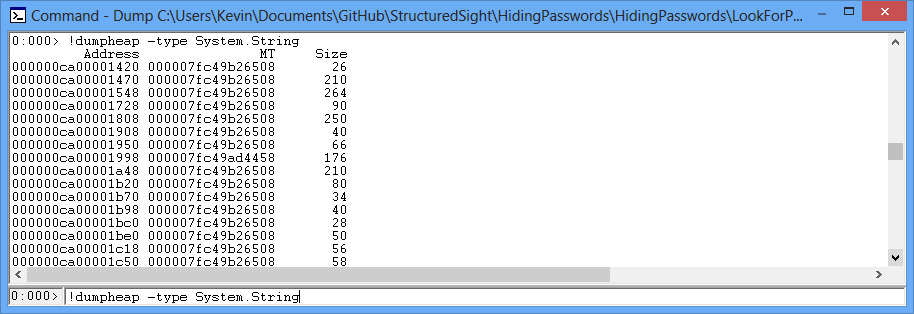

Once this is loaded, you can search the dump file for specific object types. So to get the statistics on strings (System.String):

!dumpheap -type System.String

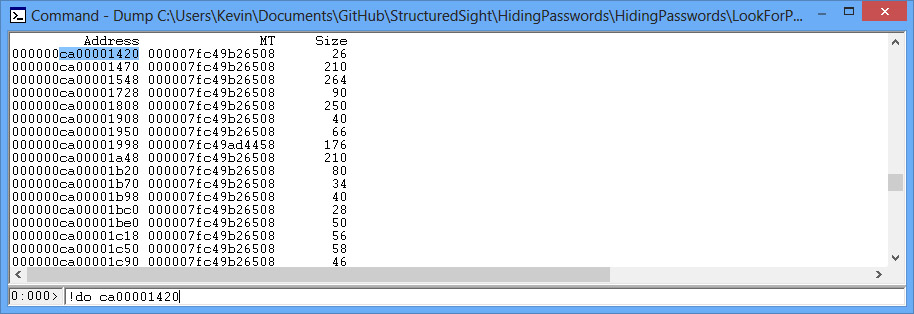

This command will display a lot of information about the methods stored in the memory table, where the information lives in memory, etc. What you need to know is where the string data itself lives in memory. To access the statictics of a specific object

!do THE_OBJECTS_MEMORY_ADDRESS

For example:

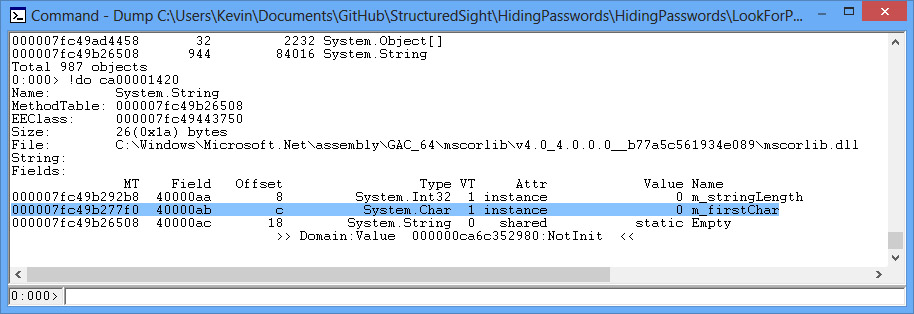

In a string object, the actual data we want to get is located at the memory address plus the offset value (which is c). You can see this by accessing the specifics of the String object by inputting the following:

.printf "\n%mu",MEMORY_ADDRESS + c

or in the example

.printf "\n%mu",ca00001420+c

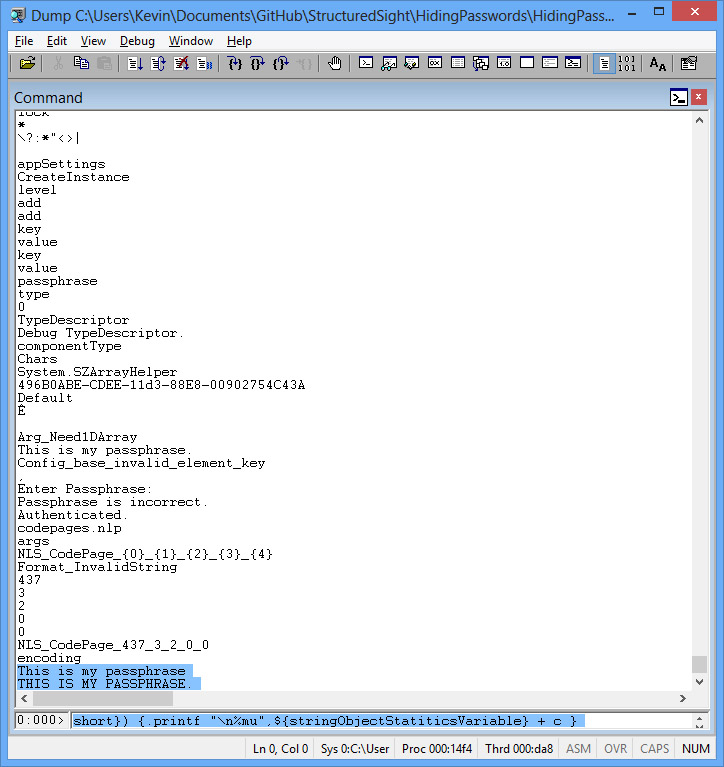

Doing this for each string in the program would be rather tedious and time consuming considering most applications are significantly larger than the example application. WinDbg solves this issue, by having a .foreach command and this loops through all the string objects and prints out the contents.

.foreach (objStatsVariable {!dumpheap -type System.String -short})

{.printf "\n%mu",${objStatsVariable} + c }

(This all goes on one line, and I've placed it on two for readability.)

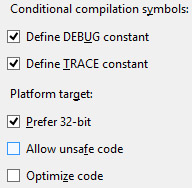

To solve the issue of attacking the program by causing a memory dump, Microsoft added the System.Security.SecureString datatype in .NET 2.0. Although effective, it has some drawbacks to it, mainly that to effectively use it, you have to use pinned objects and doing this requires to check the unsafe flag in projects.

using (var passphrase = GetPassphraseFromConsole())

{

Console.WriteLine("Your password:");

RuntimeHelpers.PrepareConstrainedRegions();

unsafe

{

var arPass = new char[passphrase.Length];

var handle = new GCHandle();

System.IntPtr ptr = System.IntPtr.Zero;

ptr = Marshal.SecureStringToBSTR(passphrase);

char* ptrPassword = (char*)ptr;

RuntimeHelpers.ExecuteCodeWithGuaranteedCleanup(

(uData) =>

{

handle = GCHandle.Alloc

(arPass, System.Runtime.InteropServices.GCHandleType.Pinned);

ptrPassword = (char*)ptr;

char* ptrArPass = (char*)handle.AddrOfPinnedObject();

for (var ii = 0; ii < arPass.Length; ii++)

{

ptrArPass[ii] = ptrPassword[ii];

}

Console.WriteLine(arPass);

},

(uData, exceptionThrown) =>

{

if (exceptionThrown)

{

Console.WriteLine("Exception thrown.");

}

Marshal.ZeroFreeBSTR(ptr);

for (var ii = 0; ii < arPass.Length; ii++)

{

arPass[ii] = '\0';

}

handle.Free();

},

null

);

}

}

Most organizations won’t allow unsafe code execution, so it makes using the SecureString pretty much pointless. With this in mind, the safest route to take for securing information is to not have it in memory at all. This removes the problem entirely. If it must reside in memory, then you can at least encrypt it while it’s stored there. This won’t solve every problem (if unsecured contents existed in memory, they still might), but it will at least reduce the possibility of it getting stolen.

The contents for the above example can be located on GitHub